Taking a moment to look away from the chaotic Puget Sound Salmon Management negotiations themselves, we wanted to look for separate, constructive, management changes that would be less controversial to implement. Our hope is to broaden the solution palette — none of the changes we’re proposing require much more than a bit of imagination and a bit of policy making. Yet these changes could uniformly improve the situation in Puget Sound and beyond.

So we’ve decided to present a series of short “Dummies”-style articles that are designed to advocate some constructive, easy-to-implement, positive steps the co-managers could be taking to improve our collective situation. None of these Dummies ideas will require huge investments of money, and all will help improve our fisheries.

The Incredible Shrinking Salmon

While lots of management decision making and hand wringing goes on about the counts of salmon, fish sizes/weights are not frequently discussed. We keep counts of individual salmon spawning, numbers released by hatcheries, and creel counts. But how big are these fish, and are things changing?

We noticed in recent years that the majority of Chinook “jacks” (typically two year old males) that we were catching during the marked selective fisheries in central Puget Sound were less than 22 inches in length. In addition some of the maturing females we were catching are often only 24 or 25 inches long. This is in stark contrast to what occurred in the 1960s and 70s. During that period on Puget Sound a jack or immature Chinook was defined by regulation to be less than 28 inches long. Mature females under 28 inches were rare. Our sense is that things are quite different today.

This idea that salmon seem to be getting smaller is backed up by data collected from 2007 thru 2014. A study of the coded wire tag data collected during the July/August Puget Sound Marine Areas 9 and 10 fisheries paints a clear picture. It shows that 70% of the 3 year old Chinook and 15% of the 4 year olds sampled in this period were less than 28 inches long. Most of today’s mature 3 year old and a sizable fraction of the 4 year old fish would have been considered jacks back in the 70’s!

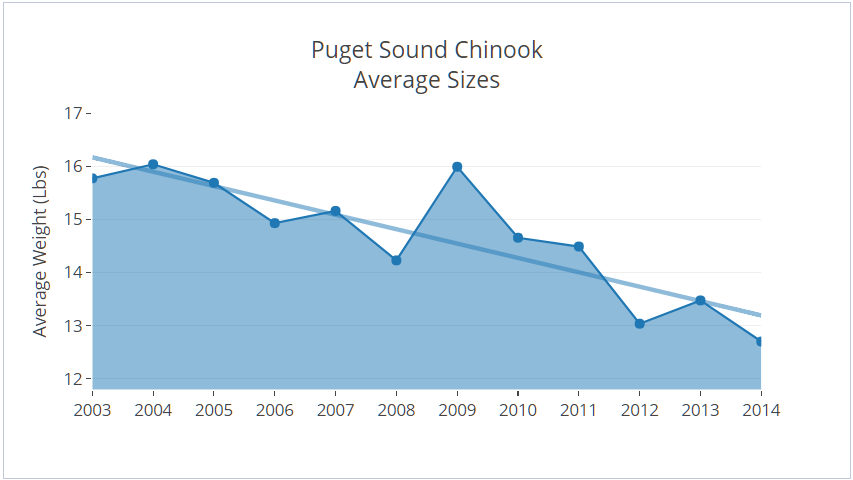

Wanting to see if a trend was visible, we hit the archives. Happily, commercial landings data collected by WDFW includes not only the numbers of fish landed, but the total weight of those fish. We have a complete set of this data from 2003-2014, and here’s the graph of Non-Tribal commercial, Puget Sound Chinook landings for that period:

It’s really startling to see such a pronounced decline. The straight line is a calculated best-fit line, and the slope of it is -0.27. In English, that means the average Chinook has shrunk by a quarter-pound each year for the last ~10 years. That’s not just surprising, it’s terrifying!

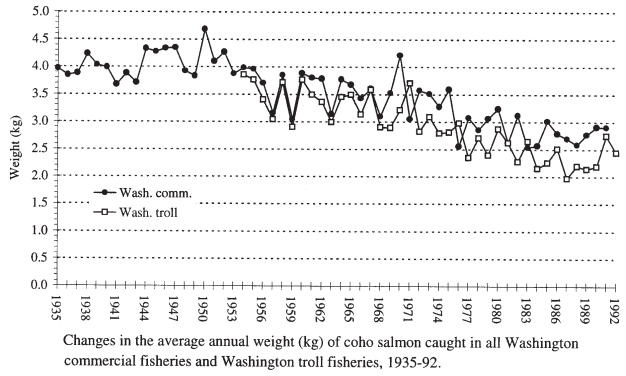

This sense of declining fish sizes does not appear to be limited to Chinook… In researching this article, we located an old NOAA report including a long-term study on Coho salmon sizes… Here’s a link to the full report, but we’ve included clearest example of similar decline in coho sizes is this chart — covering nearly 60 years of commercial coho fisheries in Washington:

Direct and Indirect Causes

Like most ecosystem problems, there’s not a single root cause of the shrinking salmon: Forage abundance is down. Net fisheries are clearly more lethal to large fish vs. small ones–and apply downward selection pressure. Sport fisherman are likely to have a retention bias towards larger fish as well. Estuary habitats are degraded. The direct effect of these and other factors has continued to depress the size of the salmon in our region. This isn’t just lines on a chart–it is a clear reduction in the sport and commercial value of the catch we do have. So not only are there significantly fewer fish to catch, the ones we are catching are smaller than ever.

But consider another, not so obvious impact of reduced salmon sizes — the impact on the food supply for Orcas and other top predators. In a situation like Puget Sound, where ensuring that an adequate food supply is available for Orcas is an important management consideration, the shrinking size of our salmon takes on added importance. As sizes diminish, top predators will have to take larger and larger numbers of fish to meet their needs — and likely expend additional energy on the pursuit. It’s a vicious cycle.

Beyond More Hatchery Fish, How About Bigger Ones?

So here’s Fisheries Management for Dummies Idea #1 — when selecting spawners at in-state hatcheries, we suggest simply selecting the biggest fish. Now this can only work if sufficient hatchery fish are returning to allow for meaningful selection, so let’s do a quick check of the numbers. Happily, a review of a recent 5 year period shows that 9 of the 10 major fall Chinook hatcheries in Puget Sound had returns double and up to 5x their brood stock needs — so it appears there are sufficient supply to select for larger/faster growing fish.

We know there are many — including state legislators and WDFW commissioners — arguing for increasing hatchery production as part of any solution to state fisheries and resident orca concerns. While we aren’t against that idea in general, we believe selecting for bigger hatchery fish will be both less expensive and less fraught with legal issues (google: Wild Fish Conservancy Lawsuit) than expanding hatchery production would be. Finally, selecting for size can be done in addition to any changes to hatchery production levels, we don’t need to choose one or the other.

From our point of view selecting hatchery fish for size a simple idea whose time has come.

What Would It Look Like?

First, we would establish a crisp management goal to measure against. We’d suggest this simple goal: Increase the average size of the adult Chinook by 3 inches. How big an impact would this be? Starting with today’s average 30 inch (typically 12 pound) Chinook, we would be targeting a 33 inch (15-18 pound) fish — a 25 to 50% increase in weight. This has the following positive effects:

- Higher quality of adult Chinook in the recreational fishery.

- Up to 50% increase in value of commercial hatchery Chinook landings for both tribal and non-tribal fishers

- Up to 50% increased forage biomass for the resident orcas.

- Fewer individual fish consumed by the orcas/predators to sustain themselves

- All the above positives come without any of the negative impacts to existing ESA runs that increasing hatchery production might have.

Best of all, this all can be done with only a minimal increase in hatchery operations and production costs. Our only question — when can we start!?!?

Question: If one of the main causes for reduced size is lack of forage food, won’t larger fish be less likely to survive/thrive in that environment? Will we end up with fewer, larger fish, but the same aggregate weight?

Excellent question — our guess is “perhaps a little”. Ecosystmes are multi-dimensional and meet the dictionary definition of complex (vs. complicated). That means that it’s quite difficult to predict outcomes with certainty for any given set of changes. Faster growing fish might also have better-than average metabolisms/digestive systems. Perhaps they have adaptations for secondary food sources on their journey. All these things are true, to some degree. There are no actions without reacions. However, we feel safe in saying the “reactions” to this particular idea appear to be more bounded than most suggestions being floated.

No matter what else you might say about gillnets, they do effectively remove the larger and arguably more fit, and more likely to survive specimens of the run. We never hear size selection discussed. So, is there a cause and effect here? The answer seems too obvious, so I will tend to believe there is until and unless hard data says otherwise. Thanks for bringing this to the fore.

You will never see huge fish again, especially when you have the nets strung clean across rivers that have tribal netting on them… for instance the nooksack river in whatcom county had 17 tribal nets ( nooksack tribe and the lummi tribe )in it for weeks, perhaps the most shocking information is that the nets went into the river in mid APRIL and went all the way till January of this year… the only time they are removed is during high water events such as heavy rains… yes fish make it to the hatcherys at a fraction of what they could be due to the span, and time they are in the river… and let’s not forget about the cook aquaculture net pen release where the tribes ( lummi’s ) effectively blocked water ways such as the nooksack, samish, skagit, California creek, Dakota creek, whatcom, bellingham bay and other water ways for 2 entire weeks 24/7 “ saving “ the rivers from the Atlantic’s… There has NEVER been an accurate count of any by-catch by the tribes on record to state their catch… We watched wdfw pull the net that was strung across the bridge at Bayview Edison road and the net was filled, we watched the 100’s of king salmon making a wake thru the water like torpedos headed up river…. Get rid of the gill nets in the rivers and see how the fish rebound….

Art, since you sound like you spend a lot of time on/near the rivers, we’d suggest you sign up to get the notifications on tribal fisheries thru WDFW, by emailing TreatyFishRegs@dfw.wa.gov Then you will know for sure when nets are in place outside of approved seasons. We encourage all readers to report all poaching activities — regardless of the user group. You can alert us at tips@tidalexchange.com too.

I used to volunteer at an urban Puget Sound Chinook hatchery and they made no attempt to select for larger fish when spawning. I asked about that, and was told that they don’t do it. Why not? Size is an important factor in natural spawning selection. Why not select for size in a hatchery. Easy to do and at no additional cost.

A healthy population of salmon is based upon diversity. That’s why hatchery managers use random selection for broodstock and mating protocols, and collect broodstock throughout the run period (for run timing diversity) rather than doing all collection at one time. Targeting specific features in the broodstock collection and mating process, as you propose, decreases diversity. Tends towards a monoculture. It would make for a less healthy population. A bad idea, especially for integrated hatchery programs. The use of randomized collection practices is a well known and widely accepted protocol. This would have been pretty easy to research before coming up with that proposal.

Sven,

While we believe biodiversity is of course important, it’s not the ONLY consideration—and selecting bigger (arguably better adapted to the current environment) fish could be argued to improving the health of the run. Natural populations of almost every species of animals place frequent biases towards size and health of the parents during reproduction, and “ensuring” the weaker/smaller spawners are equally represented could in part be responsible for the continued decline of the average fish sizes. Additionally, we’ve pointed out that harvest techniques for hatchery fish, especially gillnets, artificially inflate the stock composition of smaller fish — which our proposal would help mitigate.

We are challenging the “widely accepted protocol” because we believe it should be revised, hence the article.

The problem I have with your article is this:

1. Your “Dummies” meme suggests that their are easy, well thought out solutions that the dummy fishery managers should just implement. That’s a bit smug, unless you have a strong case. Do you?

2. It doesn’t seem so, because you cite no peer reviewed studies supporting your “select for bigness” hypothesis. It’s just a hunch.

3. Yet your hunch is launched in the face of tons of evidence that selective breeding for a single desired trait actually makes a population weaker.

4. Maybe hatcheries as a human intervention are part of the problem, and maybe your solution just makes it worse. Here’s a link to a recently issued study talking about the complex set of problems that may be leading to smaller Chinook. No mention of “just breed them bigger” as the obvious problem…

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/faf.12272/full

1. Hmmm. Maybe you should read a Dummies book. They are SIMPLIFICATIONS of complex topics for mass consumption.

2. There are 2 points to our story. First is that that sizes are dramatically shrinking — a topic not widely discussed and worthy of highlighting. Our “hunch” (your word) proved correct there as you point out there was recently a very authoritative study that confirmed this statewide. Our second point was to suggest a solution and goals. You might not like that suggestion, but our goal is to make them.

3. Conceded provisionally — if you’ll concede that gillnet and to some degree recreational fishing have in fact been for years putting the exact opposite selection pressure on hatchery fish survival. Isn’t it at least considering that we could offset years of that bias by trying this?

4. We’re the first to admit that Hatcheries aren’t a magic bullet — but so long as we’re going to have them it seems worthwhile to consider plenty of options on how they are managed. You are surely aware that some will argue for changes to the number of hatchery fish released to try to address needs for larger biomass. Would you prefer that vs. our proposal?

1. Picking the right path forward won’t be inherently simple, so the Dummies meme seems inapt. I’m sticking to that critique. Solutions won’t be simple and we can’t just throw spaghetti on the wall and see what might stick based upon hunches. (PS – NOAA wouldn’t approve an HGMP for hatcheries on that basis either) But kudos for arguing we should be thinking out of the box.

2. Kudos for pressing the fish are getting smaller angst. We should be paying attention and asking what is happening and how to address it. The paper I linked supports that very position (pay attention, figure it out, then take considered action).

3. Agree, fishing gear, and techniques, both commercial and recreational, could be part of the problem. Taking action to adjust fisheries and fisher behavior that select out larger fish is likely part of the solution. The study I linked discusses that.

4. I think hatcheries, deployed thoughtfully with conservation as the first order of business, are a necessary part of our future, including maintenance of responsible fisheries. But I won’t support a hatchery operation proposal that isn’t based upon careful scientific consideration. So the Dummies route – if that means just deploying a simple to implement action based upon a hope and prayer – seems like a bad idea.

Ernie Brannon (Senior), as the story goes, was manager of the Dungeness Hatchery. The story is that they used to capture big Elwha fish years ago and bring them to the hatchery for breeding. If possible, you might want to see what the results were (the Dungeness River is currently having low returns). Dr. Ernie Brannon (professor at UW Fisheries) also brought some Elwha fish to the UW hatchery for breeding. I don’t know what the outcome of that was, but it might be interesting to find out.

I’m all for producing bigger fish, however I believe times have changed a bit for hatchery production. In the past, I think they did use to select larger fish for hatchery reproduction. Problem with that was, we didn’t know as much about genetics as we do now. Size in fish has been linked to genetics(I can’t site where I’ve read that and won’t for a mere message thread, but if you dig around you should be able to find something on it), this isn’t always the case, but there is a link between the two. Now if you select all the big fish to use for your reproduction, your most likely going to end up picking up brothers and sisters and potentially breed those with each other, they tend to take 3 or 4 cups of sperm and mix it all together to fertilize one batch of eggs.

They did this years ago and ended up with unsuccessful stocks and are now trying to purge those stocks and replace them with broodstock programs and genetic analysis pre-fertilization, which is great. One item I think you missed on this article is bigger fish tend to produce more eggs, so you hit it on the head with less work for larger fish.

Something that does trouble me that I would love to see addressed in an article by you guys, is the evolution of hatchery programs. Most of this is before my time, but I believe most hatchery programs were introduced as a stock recovery program. Supplement the wild fish with broodstock fish, paying close attention to genetics, and letting those supplement fish breed with the natural population in ordered to boost wild reproduction, in hopes of building the run the natural run to the point we don’t need hatcheries anymore. Taking a look at this years forecast, we only have about 27,000 wild chinook returning to the Puget Sound, that’s serious cause for concern. Those are the fish we need to make more fish in order to have healthy populations with genetic diversity. It’s a serious uphill battle from here.

Sorry for the long reply.

Ross, thanks for the comments. We’re aware of concerns about reduced genetic diversity, but we’d be more receptive to these arguments if they were discussed alongside the counter-points we’ve made in the comments threads here (reversing decades of harvest bias for larger fish, and many/most wild ecosystems biasing in favor of size). Additionally, as you suggest there are selection techniques within larger fish populations which can significantly mitigate these issues.

As for hatchery introductions — many/most were put in place as mitigation for development of habitat. We know now that mitigation bargain wasn’t such a good one. Stay tuned, we have another big article on habitat coming next!

On Ross’s reply, there are tons of information in the UW library and WDFW sources about the history of hatchery production in Washington State. There were many outplants, even some from the Columbia River to Puget Sound (if I remember correctly).